Allan Houston

When true basketball enthusiasts speak of Allan Houston, the label pure shooter typically spills from their lips as they pay homage to the two-time NBA All-Star’s phenomenal shooting game. Some of today’s NBA greats might argue that their baseline turnaround jumper is better than Houston’s, but very few can prove it. With unrivaled focus and dedication, he brought an extraordinary work ethic to his venerable twelve-year NBA career, finishing as one of the league’s all-time greatest long-range shooters and one of the all-time leading scorers in Knicks history. As a preeminent figure in basketball, he demonstrated a sense of maturity and selflessness that eludes many players. He was recognized for four straight years as one of The Sporting News’ “Good Guys in Sports” and helped Team USA bring home the gold medal in the 2000 Summer Olympic games in Sydney, Australia. But for all of his on the court success, Houston’s extraordinary work off the court makes him a distinguished figure in the civic and philanthropic communities.

Houston, now forty-two, is in the second phase of his basketball career as the New York Knicks' assistant general manager. He is also principal and co-founder of the Allan Houston Legacy Foundation, a non-profit entity with year-round programming that focuses on family, mentoring, and relationship building between fathers and their children. Houston was named father of the year by the National Fatherhood Initiative in 2007. In 2011 he received the President’s Council on Service and Civic Engagement Award from President Barack Obama’s administration.

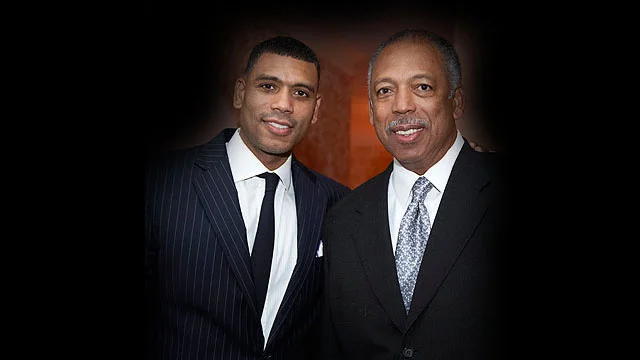

Houston is especially proud to have his father and mentor, Allan Wade Houston, Sr., by his side as a member of the Allan Houston Legacy Foundation management team and his de facto wingman. Houston’s father has fueled his love for basketball and his desire to succeed since he first picked up a basketball at age six. He draws from the life lessons his father taught him and looks to his father for advice on how to make the greatest impact in the lives of countless families. To understand where Houston’s extraordinary sense of integrity, exemplary values and overall greatness comes from, one only needs to peer into the window of his father’s life to witness an undeniable legacy of leadership.

In the midst of building a tremendous legacy as a college coach, Wade never lost sight of his most important job—being a husband and father. To this day, Houston cherishes the times with his dad growing up. He recalls sitting on the couch when he was a young kid watching boxing while his dad cut his hair. His also remembers that his father wasn’t afraid to give him a hug, show affection, and tell him, I love you. These experiences with his father fueled Houston’s confidence and taught him that he had to look no further than his own family to feel loved and supported. “He's very humble man who doesn't have to say a lot, but whatever he said, it's like gold because he backs it up with his actions,” Allan says.

As a standout high school player, Houston had his sights set on playing college basketball for his father. During his senior year, Houston signed a commitment letter to the University of Louisville where his dad was assistant coach. He was thrilled to have a chance to fulfill his dream of playing college ball for his father, but in a twist of fate, months later Coach Houston was named head coach of the University of Tennessee’s basketball program, making him the first black head coach in the Southeastern Conference (SEC).

“When I played in the NBA, people in the professional ranks of basketball — from referees to coaches, from managers to players — would say that my dad is one of the classiest men they’d ever met. For me, this is very consistent with the example he set and what I saw growing up.”

To see Wade face blatant discrimination when hostile crowds yelled racial slurs was a difficult lesson for Houston, but it taught him a great deal about his father’s character. Going to small southern towns where bigotry loomed large and playing in front of racist fans was difficult for him not only as a player but also as the son of the head coach. “Just going to Starkville, Mississippi and sensing the tension and hearing stuff about my dad was tough, but it fueled me a lot too,” Allan says. “I combated this negativity by turning my level up a little bit because I wanted him to succeed.” Houston admits, however, that he wasn’t mature enough spiritually or emotionally to forgive and get past it. He held on to a lot of anger during his time as a University of Tennessee Volunteer, but he knew he had to put his anger aside and get the job done on the court.

During Houston’s sophomore year in 1991, the Volunteers played extremely well in the SEC tournament and made it to the championship game. At the end of one of those memorable games, Houston went up and hugged his dad. This moment stands out for him because it summarized everything they had gone through that season—all of the hardships as well as the sanguine moments. “I just remember that embrace being real cool because we won the game and games in the tournament when we weren’t expected to,” Allan reflects. “I never felt closer to my father.”